SIFs, PSIFs, & Preventing SIFs

The Concept of a SIF

What is a SIF? A SIF is a Serious Injury or Fatality. The terminology was developed in the mid to late 2000s when several industry groups started looking at why fatalities weren’t declining as fast as less serious injuries. Fred Manuele wrote about SIFs in the December 2008 edition of Professional Safety. I talked about SIFs and SIF prevention in 2013 at the Global TapRooT® Summit. But the topic has gone through many iterations since then.

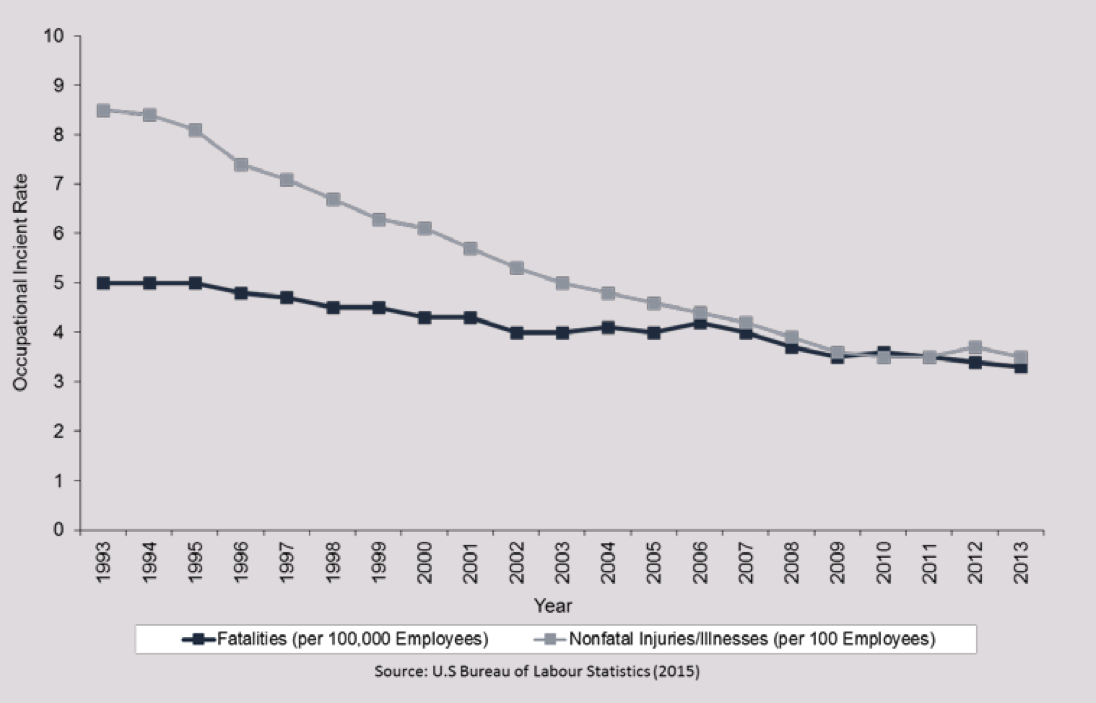

Here is a graph from a 2015 article in Professional Safety titled Preventing Serious Injuries & Fatalities that demonstrates the mismatch of trends that got the discussion started:

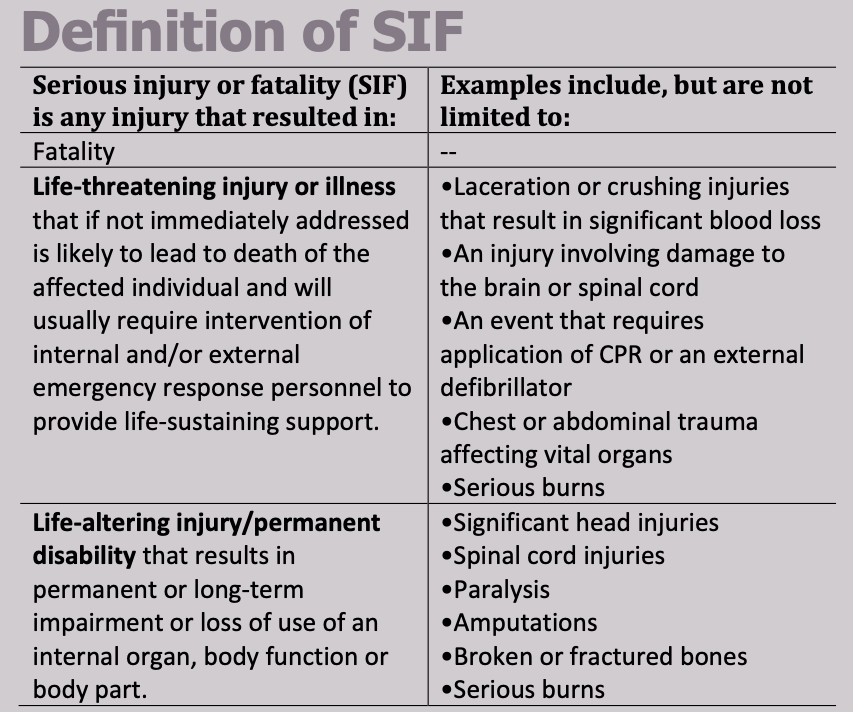

That same article defined a SIF as…

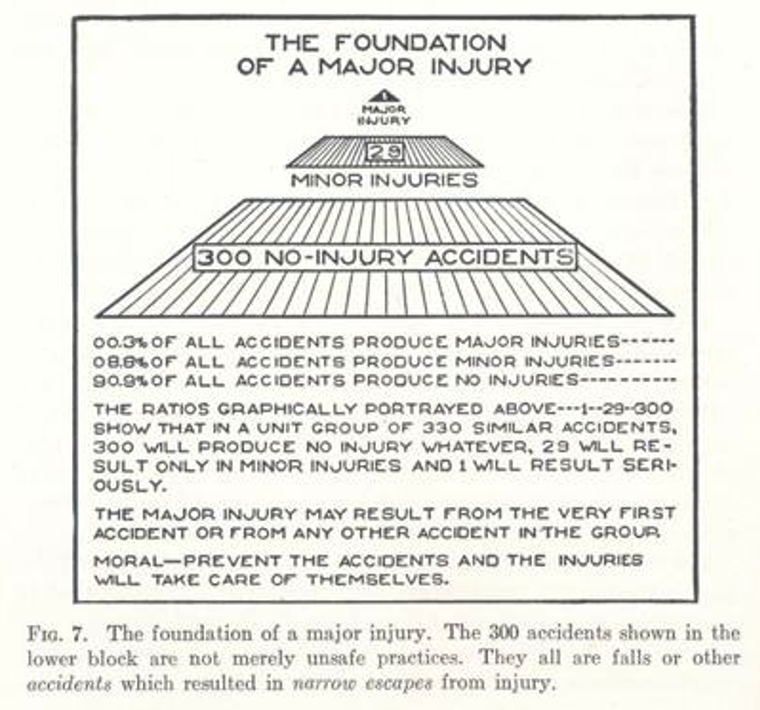

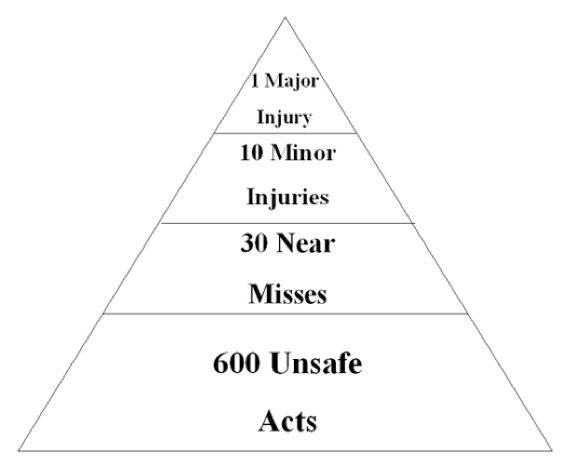

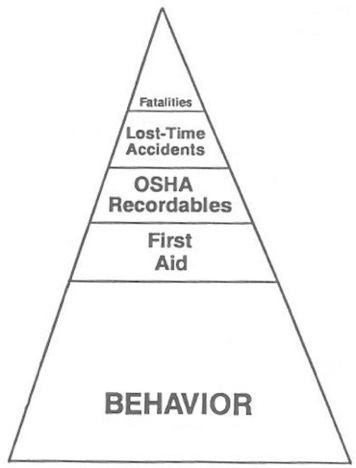

The people researching SIFs questioned the accident pyramids used at the time, including these pyramids…

Heinrich’s pyramid from 1920s and 1930s data:

Bird’s pyramid from the early 1960s:

Krause, Hindley, and Hodson’s pyramid from 1990:

They questioned whether the causes of the Behaviors, Unsafe Acts, or No-Injury Accidents had the same causes as the Fatalities, Major Injuries, or Major Injury at the top of each pyramid.

Note: If you observe the pyramids closely, they changed over the years. Heinrich wrote that the base of his pyramid (300 No-Injury Accidents) was from accidents similar to the minor injuries and major injuries at the top of the pyramid, and the “no-injury accidents” were:

“… not merely unsafe practices. They are all falls or other accidents

which resulted in narrow escapes from injuries.”

Thus, they could have caused injuries if slightly different circumstances had occurred. Therefore, they have similar causes to minor injuries or major injuries that are further up the pyramid. This is a significant difference from the two more modern pyramids that don’t claim that all 600 unsafe acts or behaviors could have caused fatalities or major injuries.

I remember in 1985, my boss at Du Pont (Rod Satterfield) and I were discussing the pyramid concept. He wondered what incidents required a thorough root cause analysis. Were some incidents too minor to investigate? Were the causes of minor incidents similar to major accidents? Would the corrective actions from the investigation of minor incidents stop major accidents?

We decided the causes of paper cuts would not be the same as the causes of major process safety incidents. At that time at Du Pont, there were almost zero major accidents (what we would now call a SIF). And we were focused more on process or reactor safety incidents. We were pretty sure that the actions taken by Du Pont to achieve an amazing industrial safety record were not the same actions required to achieve the performance of a high-reliability organization (for example, Admiral Rickover’s Nuclear Navy).

So what happened in many other industries that focused on stopping minor incidents? People started to believe that focusing on unsafe acts or behaviors could prevent major accidents without considering if the things they were focussing on could actually cause a major accident. The whole industry of behavior-based safety focused on “unsafe acts” or “unsafe behaviors” with audits and observations. Many of these behaviors would, in general, not cause a major accident. And the number of minor incidents reported was reduced (as shown in the graph above).

When you focus on something, you often get improvement. Or at least the appearance of improvement. This is especially true if you link financial compensation to improved results. And this might explain why non-fatal injuries decreased much faster than fatalities.

I remember back in the late 1990s, talking to a worker on an offshore oil platform. He said that on one particularly important turnaround, management decided to give the workers a $5000 bonus each IF the work was completed in less than 30 days. But one of the safety managers objected. The safety manager said this could lead to unsafe acts. So, management changed the bonus programs to require the work to be completed in less than 30 days with NO lost time injuries.

The person I was talking to explained that he broke his leg while on that job. It wasn’t a severe break. He said he was smuggled ashore and treated by a doctor that thought this was an injury sustained while he was working at home. His buddies on the platform covered for him so that no one in management realized he was gone. And everyone got their bonus. He said he was lucky. I asked why he said that. He replied:

“I certainly didn’t want to be the reason why everyone lost their bonus.

People out here will kill you for $5000. I only got a broken leg.”

So, perhaps at least a fraction of the injuries trended in the graph above were under-reporting of the less serious injuries. (After all, you just can’t cover up a fatality.)

SIF Programs

It wasn’t long until people started suggesting new ways to focus on fatalities and significant injuries. For example, members of a European group (Serious Accident Prevention Discussion Group) came up with a list of “Golden Rules” (sometimes called the “Life-Saving Rules”) that, if followed, would significantly reduce serious accidents and fatalities. Here are several examples of the rules (the rules varied slightly from one company to another):

Ten Life-Saving Rules:

- Work with a valid permit when required

- Obtain authorization before entering a confined space

- Verify isolation and zero energy before work begins

- Obtain authorization before overriding or disabling safety controls

- Protect yourself against a fall when working at height

- Plan lifting operations and control the area

- Follow the rules for working in toxic gas environments

- Follow safe driving rules

- Keep yourself and others out of the line of fire

- Control flammables and ignition sources

Nine Life Saving Rules:

- We will drive safely and without distraction

- We will use the appropriate Personal Protective Equipment

- We will conduct a pre Job Safety Analysis (JSA)

- We will work with a valid work permit when required

- We will obtain authorization before entering a confined space

- We will verify isolation before work begins

- We will protect ourselves against a fall when working at heights

- We will follow prescribed lift plans and techniques

- We will control excavations and ground disturbances

Seven Golden Rules

- Hazard Management – I will complete a hazard assessment before starting work and reassess if conditions change and new hazards are introduced.

- Driving Safety – I will only operate a motor vehicle or mobile equipment when free from the adverse effects of alcohol or any substance that causes impairment.

- Confined Space Entry – I will confirm the atmosphere has been tested, is monitored, and a plan is in place before entering a confined space.

- Ground Disturbance – I will verify the location of buried utilities through surface locating and positive identification before conducting a mechanical excavation.

- Lockout/Tag-Out – I will verify isolation and zero energy before work begins on energized or pressurized systems.

- Reporting of Safety-Related Incidents – I will immediately report significant safety-related incidents.

- Bypassing Safety Controls – I will obtain authorization before overriding or disabling safety-critical equipment or controls.

Ten Life-saving Rules

- Obtain authorization before entering a confined space

- Protect yourself against a fall when working at height

- Work with a valid permit when required

- Verify isolation and zero energy before work begins

- Keep yourself and others out of the line of fire

- Obtain authorization before disabling or overriding safety controls

- Follow safe driving rules

- Control flammables and ignition sources

- Plan lifting operations and control the area

- Be in a state to perform work safely

These examples are from three different companies and one professional organization. But you can see that the examples above are very similar. Maybe they could be summarised in one overall rule…

Follow the Rules!

Or maybe…

Follow the Important Rules!

Thus, it seems that rule enforcement at the “pointy end of the stick” is the emphasis behind this method of preventing fatalities. Often these rules were said to be “a fireable offense” if they were violated.

However, the document mentioned earlier (Serious Injury and Fatality Prevention) had this warning, that:

“… made it clear that implementing “Golden Rules” or “Life-saving Rules”

was not sufficient for tackling SIF prevention. However, this type of initiative

does go a long way to changing mindsets, or even the company’s

culture, by placing focus on SIF prevention.”

Reporting of Potential SIFs

To prevent SIFs, organizations have implemented reporting of potential SIFs so that they can be investigated and the root causes of the potential SIFs can be addressed. However, if breaking the Life-Saving Rules is a potential SIF and violating a Life-Saving Rule is a fireable offense, the worker might find themselves in a conundrum. Should they report something where no injury has occurred, and they already know what to do to prevent a future accident (follow the rule next time), and if it is reported, someone could get fired? It could be your buddy who gets fired. It could be you.

So, some say you shouldn’t fire someone for violating a Life-Saving Rule when the violation is voluntarily reported. But if violating a Life-Saving Rule is NOT a fireable offense, how can management enforce the rules?

Therefore, some organizations add “reporting significant safety-related incidents” to the Life-Saving Rules, and then violating that rule (not reporting a potential SIF) is a fireable offense (as you might have noticed in the Seven Golden Rules above).

To reduce the impact of every potential SIF being a fireable offense, companies could institute a “progressive” discipline system that doesn’t require firing an employee for a first offense. It takes multiple violations to get fired as a punishment.

Obviously, enforcing the rules and reporting potential SIFs is a catch-22 for management and the employees. However, to achieve improvement, it is almost universally recognized that potential SIFs must be reported and analyzed to correct “drift” in the system and stop the normalization of deviation.

What Must Be Reported?

The next difficulty with implementing a SIF reduction program is what needs to be reported and investigated. It wasn’t too long after the Life-Saving Rules were invented that management realized that not all violations of the Life-Saving Rules resulted in a SIF. Not only that, but some violations never resulted in a SIF. And some SIFs could happen despite the workers’ best efforts to follow the rules.

Thus, what incidents need to be reported and investigated, and which ones either didn’t need to be reported or didn’t need to be investigated? We wrote several articles about this in the past, including:

- Heinrich Pyramid Discussion – Where are you? (2018)

- Do You Waste Time Investigating Minor Incidents? (2019)

- Deciding When to Investigate a Precursor Incident (What’s in the Diamond?) (2020)

- Categorization of Incidents (Three Safety Pyramids) (2022)

The secret is determining when an incident is a precursor to a SIF or a process safety accident.

That brings us to the latest work about classifying incidents to determine what should be investigated.

PSIFs and the SCL Model

Back in 2020, The Edison Electric Institute (EEI) published a first edition of a Safety Classification and Learning (SCL) Model. The model was revised and republished in December of 2021. In January of 2023, the latest model was published, titled:

Safety Classification and Learning (SCL) Model

The model springs from the work on Significant Injuries and Fatalities (SIFs) and Energy Theory by Dr. Matthew Hallowell at the University of Colorado (a Civil Engineer).

In the paper published in January of 2023, Energy Theory is used to determine which incidents need to be investigated to prevent SIFs and which ones don’t. The ones that should be investigated are PSIFs, HSIFs, and LSIFs.

What is a PSIF? It is a…

Potential to cause Serious Injuries or Fatalities

That is what we have been calling a Precursor Incident (or at least part of what we call a Precursor Incident – more about that later).

In the executive summary, the paper concludes …

“Tracking and learning from PSIF could redirect attention from lower-severity incidents to conditions that have the potential to be life-threatening or life-altering, which would be an important step toward the elimination of SIFs. In the future, the SCL model and the associated definitions could be used to form new, more impactful safety metrics that complement traditional indicators like total recordable injury rates (TRIR). This would allow organizations to monitor progress toward the most important goal: saving lives.”

Certainly, that is a worthwhile goal.

What is Energy Theory, and how can it be used to identify a PSIF? That is what the SCL Model is all about.

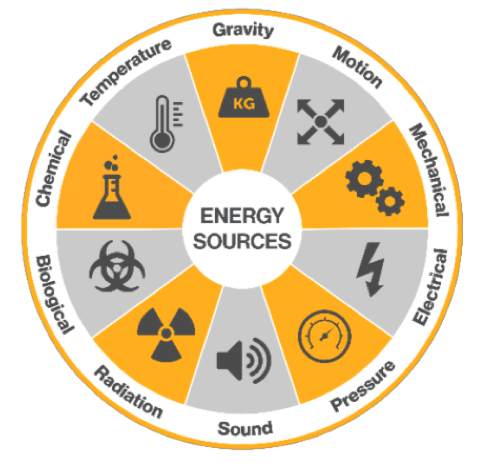

Energy Theory is that it takes a certain amount of energy to cause a fatality. These “energies” can be classified as in the figure below…

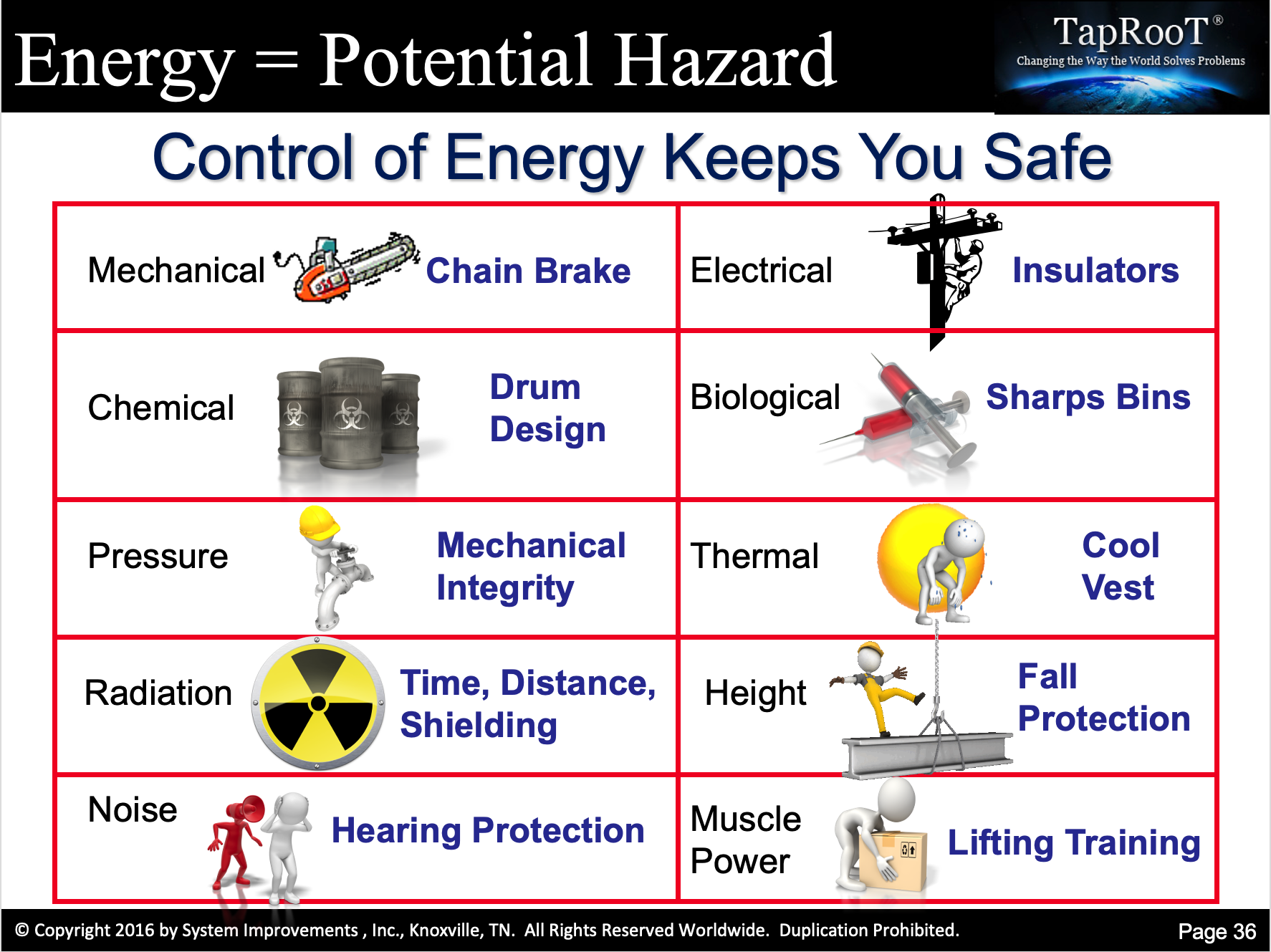

These are similar to the Hazards/Energies taught in our TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis Training for the past 30 years…

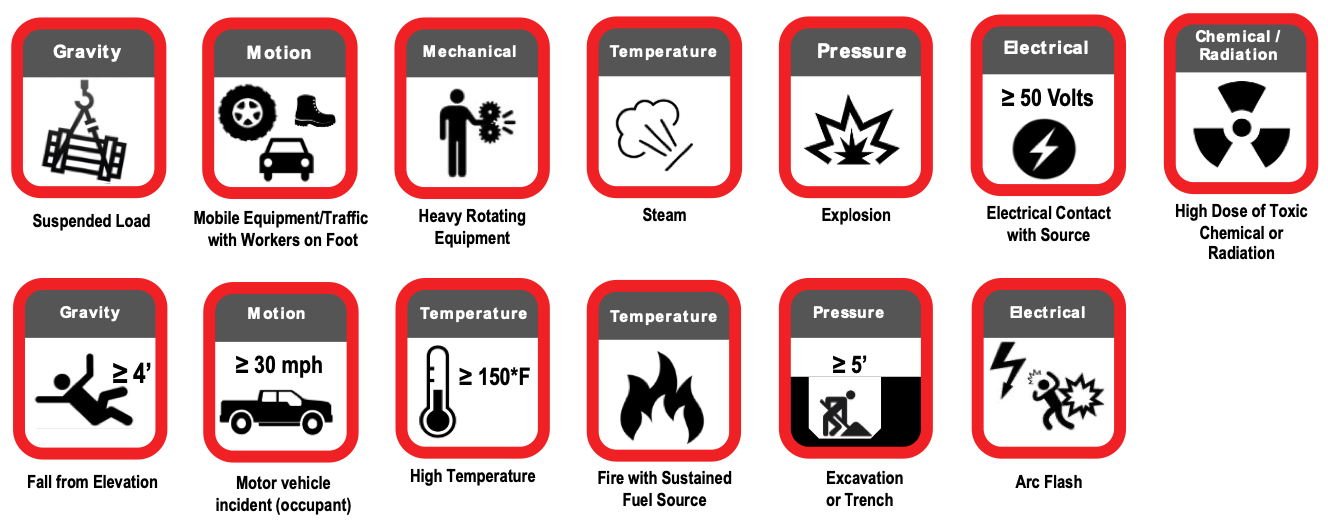

How much energy does it take to be likely to cause a fatality if the energy isn’t controlled? That depends on the type of energy. To give people a general idea, the following diagram was presented in the Safety Classification and Learning (SCL) Model paper…

But, as the paper states, these icons are not all-inclusive. Thus, the paper provides other methods to judge just how much uncontrolled energy needs to be present to cause a SIF.

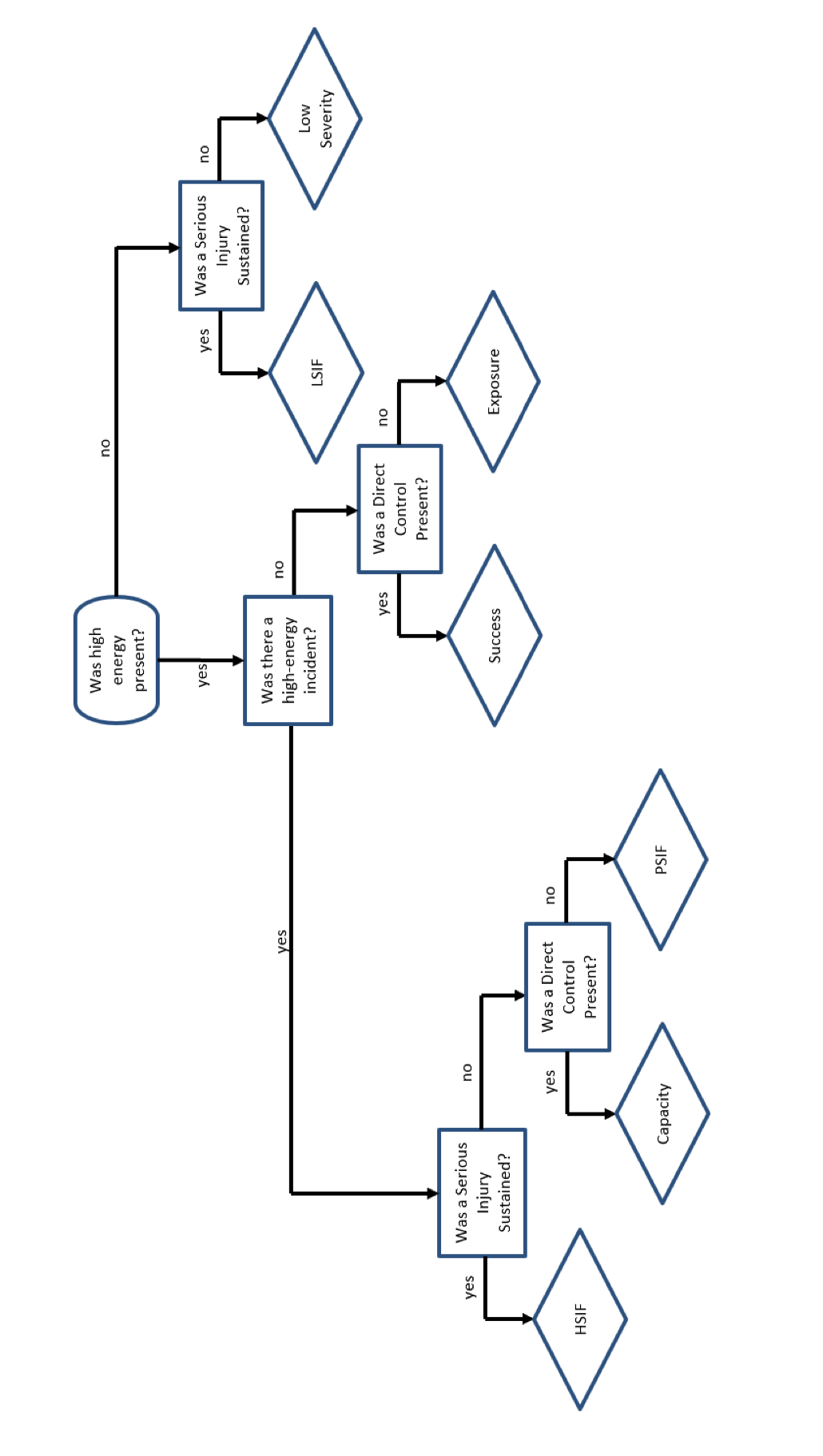

Once you can determine the energy present, you can then use the SCL Model (shown below from the paper) to judge is how much investigation is needed.

Now, what are all the acronyms used above? Here is a short set of definitions from the paper…

HSIF = High-Energy Serious Injury or Fatality

Capacity = Incident with a release of high energy in the presence of a direct control where a serious injury is not sustained.

PSIF = Potential Serious Injury or Fatality – Incident with a release of high energy in the absence of a direct control but a serious injury was not sustained.

Success = Condition where a high-energy incident does not occur because of the presence of a direct control.

Exposure = Condition where high energy is present in the absence of a direct control.

LSIF = Low-Energy Serious Injury or Fatality – Incident with a release of low energy in the absence of a direct control where a serious injury is sustained.

Low Severity = Incident with a release of low energy where no serious injury is sustained.

Direct Control = A barrier that is specifically targeted to the high-energy source; effectively mitigates exposure to the high-energy source when installed, verified, and used properly; and is effective even if there is an unintentional human error during work that is unrelated to the installation of the control.

High-Energy Incident: An instance where the high-energy source was released and where the worker came in contact with or in proximity to the high-energy source.

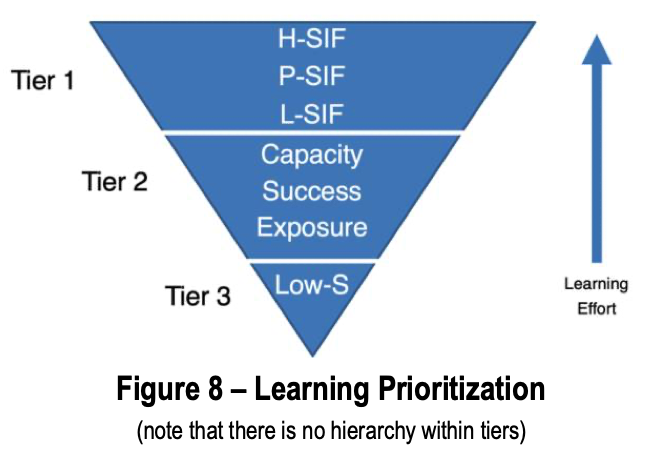

Once you have categorized the learning potential using the flow chart above, you can decide how much effort you want to use to investigate the incident, find its root causes, and develop effective fixes. This is summarized by the figure in the article that is shown below…

The SCL Model is more complex than the matrix in Book 2: TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis Implementation, Appendix A – the Problem Reporting and Investigation Matrix (Copyright © 2017). The matrix is shown below.

| TYPE | CONSEQUENCE | RESPONSE |

| Safety | Work-related pain or unsafe condition Off-the-job injury | Report Only |

| First aid required Traffic accidents with no injuries Events that caused lost work time but could not cause a serious injury/fatality | Report & Simple Investigation | |

| Fatality Injuries that cause permanent disability Lost time injuries or near-misses that could have caused a serious injury/fatality with the failure of an additional Safeguard | Report & Major Investigation | |

| Process Safety | Failure to use a process safety-related procedure Near-miss that could have caused the failure of a process safety-related Safeguard | Report Only |

| Failure of a single process safety-related Safeguard | Report & Simple Investigation | |

| Incident that could have caused a fire/release of hazardous materials if an additional Safeguard had failed Fire/significant release of hazardous materials Injury or near-misses for injury to off-site personnel | Report & Major Investigation | |

| Environmental | Noise or odor complaints | Report Only |

| Any abnormal spill or release | Report & Simple Investigation | |

| Air or water permit violations or other reportable environmental incidents Any release that requires evacuation or attracts media attention | Report & Major Investigation | |

| Quality | Near-miss that could have had an adverse effect on product quality | Report Only |

| Quality problems detected before shipment but outside the normal process control Quality problems that cost more than $10,000 but less than $100,000 | Report & Simple Investigation | |

| Quality problems that cost more than $100,000 Quality problems that adversely affect customers | Report & Major Investigation | |

| Production & Schedule | Procedure error Part failure Schedule slippage | Report Only |

| Frequent part failures Any loss, including damage & lost profit costing more than $10,000 but less than $100,000 Product delay of more than 5 days but less than 20 days | Report & Simple Investigation | |

| Any loss, including damage & lost profit costing more than $100,000 Any product delay of more than 20 days | Report & Major Investigation |

But the paper claims that people using the SCL Model and flow chart to classify their incidents are more consistent in incident classification when they use the SLC Model than when they use a model similar to the TapRooT® Problem Reporting and Investigation Matrix.

Note that the matrix from Book 2 includes many more categories than just safety (including process safety, quality, the environment, and production/schedule results). Thus, the matrix above is more comprehensive. Also, the matrix is just an example. The matrix values could be customized for a particular client. The SLC Model could even be included to classify the Safety category.

What Are You Doing to Prevent SIFs?

Perhaps the most important part of this article is:

What Are You Doing to Prevent SIFs?

I think the most important thing that you can do is to adopt the advanced root cause analysis system:

TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis

Without advanced root cause analysis, your efforts to classify incidents are a waste of time.

Why? Because it takes advanced root cause analysis and effective corrective actions to improve performance and stop fatalities.

So, targeting the appropriate incidents to investigate is good, but you must do superior investigations with the best root cause analysis system to really improve performance.

If you need to learn more about TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis, attend one of our TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis Courses.

You can see the schedule for our upcoming Public TapRooT® RCA Courses HERE.

Or CLICK HERE to get a quote for a course at your site.

If you are already a TapRooT® User, consider attending the Global TapRooT® Summit to:

- Refresh your TapRooT® Knowledge

- Learn Advanced TapRooT® Techniques

- Network with other TapRooT® Users and share best practices

- Learn the latest performance improvement techniques from industry leaders and performance improvement experts

You can’t afford a SIF. You need TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis to prevent them.

Please send newsletter to e-mail below

We are in the process of implementing the SCL and Energy Wheel at our organization. This article clearly articulates how important effective cause analysis is as part of the overall organizational improvement system. That is something we have been struggling with aligning on.

Thank you, GREAT JOB!!